Global Shield Briefing (18 February 2025)

Domestic readiness, precise threat estimates, citizen-led policy, and local response efforts

The latest policy, research and news on global catastrophic risk (GCR).

Benjamin Franklin’s contributions are innumerable. Across science, politics, diplomacy and writing. His mark is still felt. So you’d be forgiven for overlooking an early achievement: successfully advocating for fire safety.

Early 18th century Philadelphia, with its narrow streets, densely packed wooden buildings and open fireplaces, was at constant risk of fire. A relatively young Franklin decided to raise the issue. In his letter, “On Protection of Towns from Fire”, penned in his own The Pennsylvania Gazette, he made a number of admirably specific policy recommendations, like banning shallow hearths, increasing chimney cleaning frequency, requiring licenses for chimney sweepers and fining the sweeper if a chimney fire occurred soon after cleaning.

It is here, in this letter, we first encounter a now well-worn phrase in the fields of medicine, disaster and risk: “an Ounce of Prevention is worth a Pound of Cure”.

Almost three centuries on, Franklin’s advice is still ignored. We even have the statistics that prove him out: the UN’s disaster risk agency found that every dollar invested in risk reduction and prevention could save up to 15 dollars in post-disaster recovery. But response and recovery often becomes the overriding political priority and budgetary focus. Prevention is, so often, neglected.

Let’s hope, at least on global catastrophic risk, we can avoid the outcome Franklin mapped out: “when your Stairs being in Flames, you may be forced, (as I once was) to leap out of your Windows, and hazard your Necks to avoid being over-roasted.”

Acting national, hoping global

On 10-11 February, France’s President Macron hosted the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Action Summit. The “Statement on Inclusive and Sustainable Artificial Intelligence for People and the Planet” was signed by 60 participating countries, as well as the European Union and the African Union. The UK and US, however, did not sign.

The US has started the process of withdrawing from the World Health Organization (WHO), including ceasing involvement in negotiations on the WHO convention on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

The Munich Security Report 2025 was released ahead of the Munich Security Conference, a major annual international security conference held on 14-16 February. The report focuses on the shifting power dynamics at global and national levels. It notes that: “On the one hand, power is shifting toward a larger number of actors who have the ability to influence key global issues. On the other hand, the world is experiencing increasing polarization both between and within many states, which is hampering joint approaches to global crises and threats.”

Policy comment: The decline in multilateralism is a long-standing trend, one which is only being exacerbated by recent geopolitical and political shifts. So national governments must take greater responsibility for global catastrophic risk reduction. They might not be able to rely on global institutions to prevent or manage crises. And in times of global crisis, international cooperation would be even harder. Policymakers must build readiness and improve self-reliance, such as strengthening critical infrastructure, emergency response systems and national stockpiles of essential resources. The parts of government that focus on international and future threats – like foreign policy agencies and intelligence communities – must be even more alert to global risk that might quickly and unexpectedly threaten national security and human welfare. Governments must allocate budgets to disaster risk reduction, such as contingency funds and adaptive fiscal policies. And proactive public engagement and communication is key. Effective crisis response depends on public trust and engagement. For countries without robust civil defense, there is little time to waste.

Estimating with precision

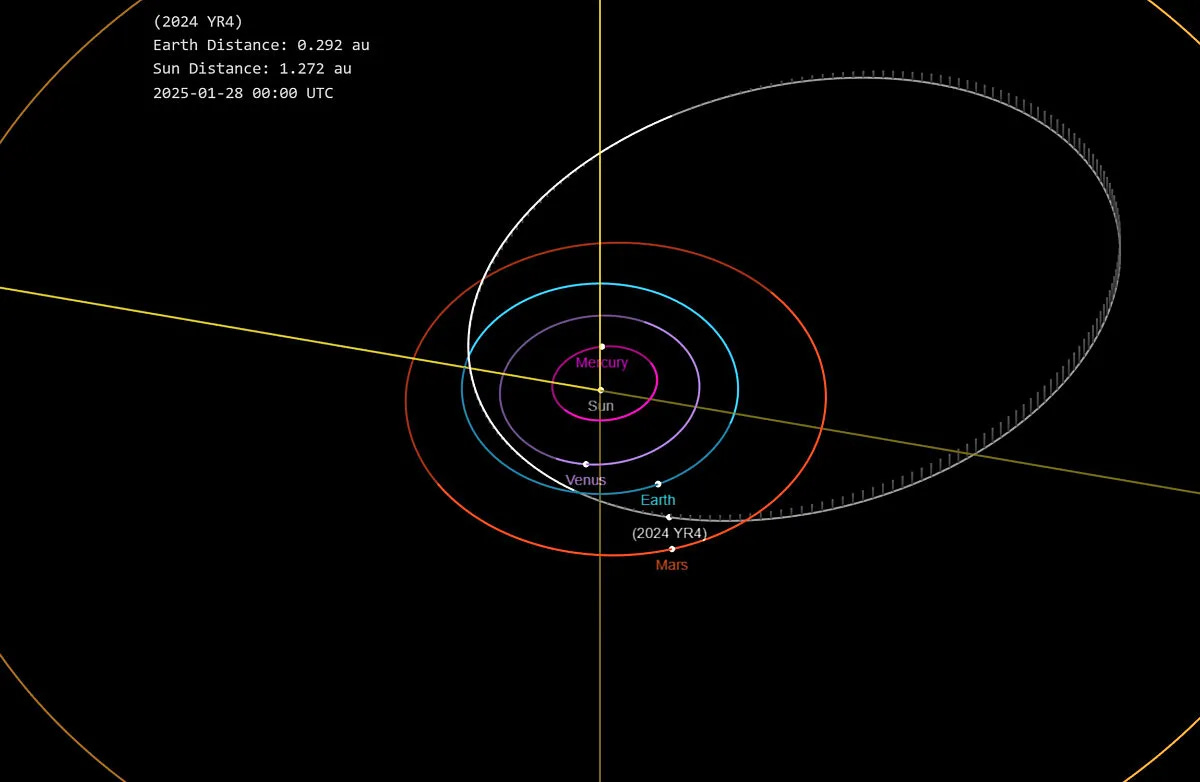

A recently discovered asteroid, named 2024 YR4, has a 2.3 percent chance of hitting Earth in 2032. Estimated to be around 40-90 metres in length, it could cause damage as far as 50 km from the impact site, which would devastate a large city. Mumbai and Kolkata in India, Lagos in Nigeria and Bogotá in Colombia are the largest that could be hit if it strikes Earth. NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope will observe the asteroid in March 2025 to better assess the asteroid’s size, and it will pass near Earth again in 2028, when its trajectory will be able to be better determined.

Policy comment: The discovery of 2024 YR4 generated a high degree of public interest over the past six weeks, despite its relatively low likelihood and long time frame. This interest is probably due to a public fascination with space, especially space objects. However, there might be another factor: specificity. Asteroid trackers can provide a date of impact, the trajectory, the potential impact zones, the impact size and, years in advance, a percentage chance down to the decimal figure. Detection of near-Earth objects receives significant international effort, with the US and European space agencies, as well as private observatories, tracking over 30,000 objects. It provides decision-makers with a high degree of confidence when assessing options to reduce the risk. No other global catastrophic threat receives this level of cooperative, international scientific effort, let alone level of precision. Of course, the tail risk of other catastrophic threats cannot be assessed with the same certainty – but governments rarely, if ever, try. For example, the public do not receive comparable statistical representations for nuclear winter, climate tipping points or severe pandemics. There are various tools to assess risk and make decisions under deep uncertainty, such as extreme value theory, simulation modelling, judgment aggregation (like forecasting competitions), precautionary strategies and scenario planning. Governments should use these tools more frequently and systemically to inform themselves and the public.

Also see:

The results from a recent forecasting competition on the probability of a nuclear incident causing up to 10 million deaths by 2045. The median forecast from a sample of the US public was 10 per cent, while the median estimated 5 per cent and the median superforecaster was 1 per cent.

A new project by UK’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA) devoting 81 million pounds to develop an early warning system for climate tipping points.

Following the public’s lead

A new opinion poll asked the UK public about a range of global catastrophic threats. About a third of respondents ranked AI as one of the issues to have the largest impact on the world, behind climate change and risk of war (about 50 percent each). It found that “Substantial majorities of respondents state that the government should be spending significant resources to prepare for catastrophic climate change (69%), global pandemic (68%), nuclear war (63%), and uncontrolled AI (57%).” Three-quarters of respondents said they would hold the national government responsible for responding to extreme risk.

Previous studies have also shown concern around global catastrophic risk and the lack of policy effort. A 2024 survey found that, within the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters, majorities supported strong climate action, ranging from 66 percent of people in the United States and Russia, to 73 percent in China, 77 percent in India and 85 percent in Brazil. A 2019 poll found that sixty one percent of adults across 26 countries opposed the use of lethal autonomous weapons systems. A 2007 survey across nuclear weapons states showed overwhelming support for the elimination of nuclear weapons or a reduction of arsenals, a result reflected more recently in the US as well.

Policy comment: Although governments are the arbiters of national security, the public’s expectation far exceeds the policy response on global catastrophic risk. The public, rather than dismissing it, is often quite concerned when asked about it. Governments need to follow their citizens' lead. They could do their own polling across a range of global threats, to understand public sentiment and perceived level of prioritization. They could establish citizen councils or groups to provide regular and detailed feedback on government action on large-scale and complex threats. They could bring a public polling component to internal national risk assessment processes. The public can also be a powerful and useful tool for developing policy; for example, the Citizens Convention for Climate was an citizen assembly announced by President Macron in 2019, leading to a set of 149 proposals. Such efforts require the government to trust these delegates and deliver on the public mandate they represent.

Supporting local response

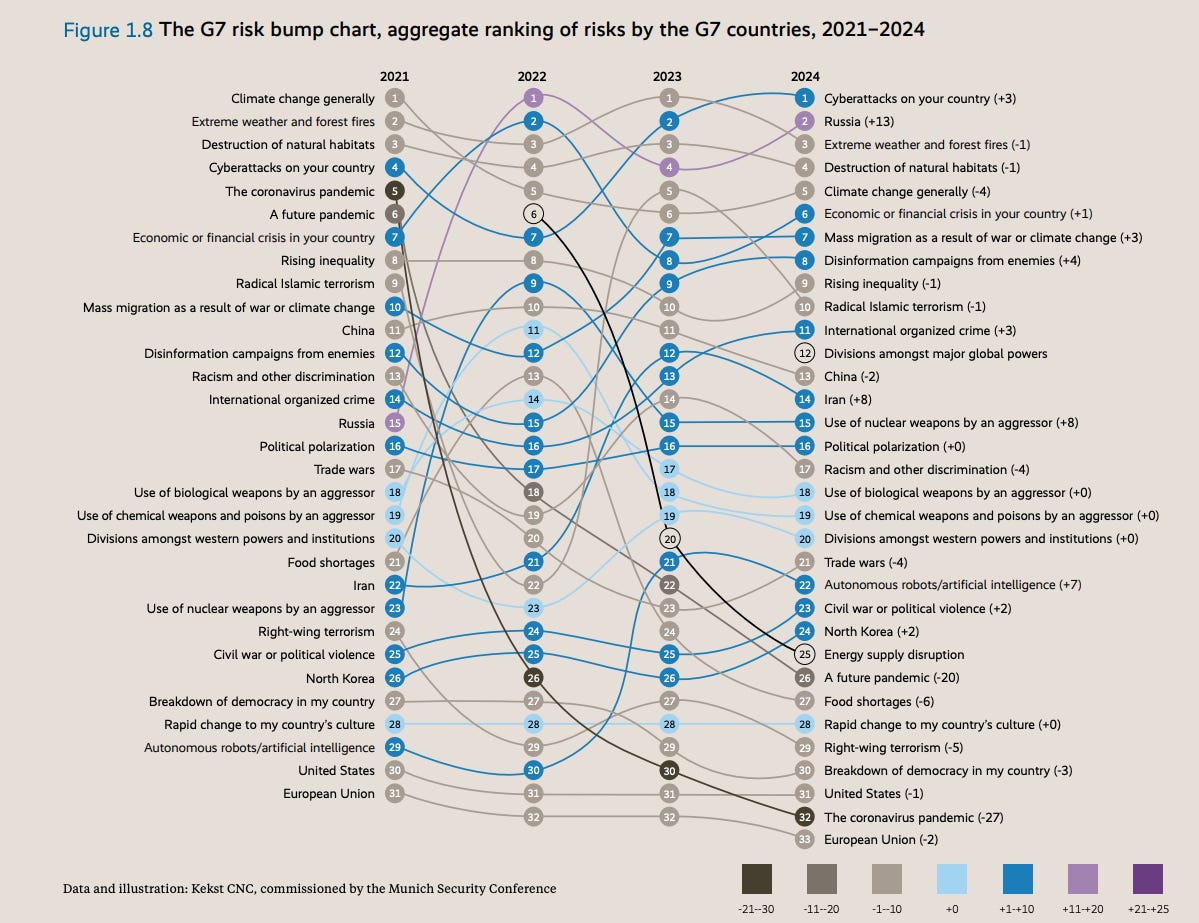

The Munich Security Report 2025 found that, among G7 countries, the risk of “A future pandemic” ranked as the sixth highest concern in 2021, but dropped to 26th (out of 33) in 2024.

The thirteenth meeting of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body to draft and negotiate the WHO convention – nicknamed the Pandemic Treaty – is being held over 17–21 February. A key concern by health experts has been the focus on preparedness or response over prevention. Completion by the target of May 2025 remains highly uncertain.

Africa is dealing with a number of outbreaks. The Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo and other parts of Africa has led to over 2500 cases, with a 67 percent fatality rate. The Sudan virus, one of the four types of Ebola virus, was recently detected in Uganda, with one confirmed death. South Sudan became the latest country in the continent’s mpox outbreak. Ebola has been ruled out in outbreak scare in Manhattan.

On 31 January, the US Department of Agriculture confirmed that it had detected a new variant of highly pathogenic avian influenza in dairy cattle – an indication that bird-to-dairy transmission might not be as rare as initially believed. In January, a 65-year old man was the first (and only so far) person in the US to die of this avian influenza outbreak, with 68 confirmed cases in total.

The Trump administration has reportedly appointed Gerald Parker to head the White House Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy. Parker is a well-respected biosecurity expert, most recently in the roles of associate dean for Texas A&M’s Global One Health program and Director of the Biosecurity and Pandemic Policy Center, as well as chair of National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB).

Policy comment: Disasters start and end locally. Whether a pandemic, a natural disaster or a conflict, the first people on the scene are locals: emergency services, community organizations, and ordinary citizens. The challenge with pandemics, much like global catastrophic threats of any nature, is that local can very quickly become global. So speed of response is crucial. The longer it takes to detect, assess and respond to emerging threats, the greater the human and economic toll. Part of speed is agility and coordination across multiple levels of governance – local, national, regional and international. Higher levels, particularly the federal level, must empower local authorities with resources, guidance and coordination mechanisms for when a crisis happens. Governments must develop early-warning systems, prepare well-tested plans, and ensure timely decision-making. Funding constraints, political hesitancy and bureaucratic inertia delay critical actions. The outbreaks in Africa provide two counterpoints. On one hand, the Uganda Virus Research Institute began trials on a vaccine within days of its Ebola outbreak; on the other, the US’s recent decision around global health security could put at risk its pledge of a million mpox vaccine doses. In global catastrophic risk reduction, the weakest link determines the strength of the entire system.

Also see:

A highly informative weekly update on global pandemic news by the Pandemic Action network.

This briefing is a product of Global Shield, the world’s first and only advocacy organization dedicated to reducing global catastrophic risk of all hazards. With each briefing, we aim to build the most knowledgeable audience in the world when it comes to reducing global catastrophic risk. We want to show that action is not only needed, it’s possible. Help us build this community of motivated individuals, researchers, advocates and policymakers by sharing this briefing with your networks.